-

Luther's Works: Digital Download

The 55-volume set of Luther's Works, a monumental translation project published jointly by Fortress Press and Concordia Publishing House in 1957, is singular...

$259.00

-

Martin Luther's Basic Theological Writings: Third Edition

The best one-volume reader of Luther's writings—now revised. Martin Luther's Basic Theological Writings, a single-volume introduction to Luther's most influential...

$59.00

-

The Annotated Luther, Volume 2: Word and Faith

Volume 2 of The Annotated Luther series contains a number of the writings categorized under the theme word and faith. Luther was particularly focused on what the word "does" in order to create and sustain faith.

$39.00

-

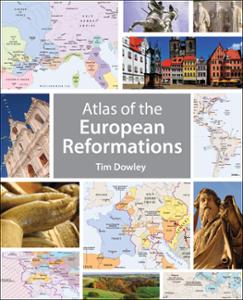

Atlas of the European Reformations

A new atlas of the European Reformations has been keenly needed. Fortress Press is pleased to offer the Atlas of the European Reformations.

$24.00

-

The Reformation to the Modern Church: A Reader in Christian Theology

Engagement with primary sources is an essential part of effective teaching and learning in the church history or theology course. And yet, pulling together and distilling the right readings can be challenging. In this all-new primary-source anthology, Keith D. Stanglin has done the heavy lifting for a new generation of classrooms. Stanglin has edited and introduced over 100 selections to create a reader that orients students to the ebb and flow of thought that moves out from the pre-Reformation period.

$49.00

-

True Faith in the True God: An Introduction to Luther's Life and Thought, Revised and Expanded Edition

True Faith in the True God meets the deep need for a clear and concise introduction to the life and teachings of the great church reformer, Martin Luther.

$44.00

-

The Theology of Martin Luther: A Critical Assessment

Does Martin Luther have anything to say to us today? Nearly five-hundred years after the beginning of the Reformation, Hans-Martin Barth explores that question

...$39.00

-

Martin Luther's Theology: Its Historical and Systematic Development

This definitive analysis of the theology of Martin Luther surveys its development during the crises of Luther's life, then offers a systematic survey by...

$39.00

-

Luther Refracted: The Reformer's Ecumenical Legacy

Luther Refracted speaks to the currency that Luther’s life and thought continue to enjoy in today’s Christian reflection. The contributors, representing a variety of Christian denominations, demonstrate Luther’s impact on their own traditions and, together with the Lutheran respondents, encourage a fresh understanding of the Reformer.

$44.00

-

The Honeycomb Scroll: Philipp Melanchthon at the Dawn of the Reformation

Long overshadowed by Luther and Calvin, Philipp Melanchthon (1497-1560) is nevertheless one of the most important figures in the Protestant Reformation. Reformer, humanist, theologian, philosopher, ecumenist, and teacher of pastors--Melanchthon had a profound effect on the sweep of Western church history.

$44.00

-

Luther on Faith and Love: Christ and the Law in the 1535 Galatians Commentary

The project argues that in the discussion of proper righteousness and holiness, Luther's redefined love emerges in harmony with faith.

$59.00

-

Martin Luther, the Bible, and the Jewish People: A Reader

The place and significance of Martin Luther in the long history of Christian anti-Jewish polemic has been and continues to be a contested issue. It is true that Luther's...

$26.00

-

Deviant Calvinism: Broadening Reformed Theology

Deviant Calvinism This book contributes to theological retrieval within the Reformed theology, and establishes a wider path to thinking Calvinism differently. It seeks to show that the Reformed tradition is much broader and more variegated than is often thought.

$8.50

$34.00Save 75%

-

A Case for Character: Towards a Lutheran Virtue Ethics

Contemporary Lutheranism has struggled with the appropriate place of morality and character formation, as these pursuits often have been perceived as being at odds with the central Christian doctrine of justification. A Case for Character explores this problem.

$32.00

-

Dominus Mortis: Martin Luther on the Incorruptibility of God in Christ

This work creates the conditions necessary for an alternative appropriation of Luther's Christological legacy. By re-specifying certain key aspects of Luther's Christological commitments, Luy provides a careful reassessment of how Luther's theology can make a contribution within ongoing attempts to adequately conceptualize divine immanence.

$39.00

-

Fruit for the Soul: Luther on the Lament Psalms

It is easy to forget how often Luther’s concerns turned toward helping the common person understand and take comfort from God’s word. In this volume, Dennis Ngien helps contemporary readers engage Luther’s commentary on the lament psalms.

$34.00

-

Documents from the History of Lutheranism, 1517-1750

A unique resource: from the Reformation to Pietism. This unique collection of excerpts from Lutheran historical and theological documents - many...

$44.00

-

Martin Luther's Catechisms: Forming the Faith

Martin Luther's catechisms 3 the Small Catechism in 1528-29, and the Large Catechism in spring 1529 — responded in part to "the deplorable,...

$18.00

-

Two Kinds of Love: Martin Luther's Religious World

Published in Finland in 1983, Two Kinds of Love is the second of Tuomo Mannermaa's provocative books offering a distinctly different interpretation of Martin...

$24.00

-

Printing, Propaganda, and Martin Luther

Mark Edwards's pioneering work on the Reformation as a "print event" traces how Martin Luther, the first Protestant, became the central figure in the...

$29.00

That the Baptism of infants is pleasing to Christ is sufficiently proved from His own work, namely, that God sanctifies many of them who have been thus baptized, and has given them the Holy Ghost; and that there are yet many even to-day in whom we perceive that they have the Holy Ghost both because of their doctrine and life; as it is also given to us by the grace of God that we can explain the Scriptures and come to the knowledge of Christ, which is impossible without the Holy Ghost. But if God did not accept the baptism of infants, He would not give the Holy Ghost nor any of His gifts to any of them; in short, during this long time unto this day no man upon earth could have been a Christian. Now, since God confirms Baptism by the gifts of His Holy Ghost as is plainly perceptible in some of the church fathers, as St. Bernard, Gerson, John Hus, and others, who were baptized in infancy, and since the holy Christian Church cannot perish until the end of the world, they must acknowledge that such infant baptism is pleasing to God. For He can never be opposed to Himself, or support falsehood and wickedness, or for its promotion impart His grace and Spirit. This is indeed the best and strongest proof for the simple-minded and unlearned. For they shall not take from us or overthrow this article: I believe a holy Christian Church, the communion of saints.